STL Blues Detectives

Written by Bob Baugh

Published Dec.2018/Jan.2019 issue of

Big City Rhythm and Blues

Charlie O’Brien, Blues Detective

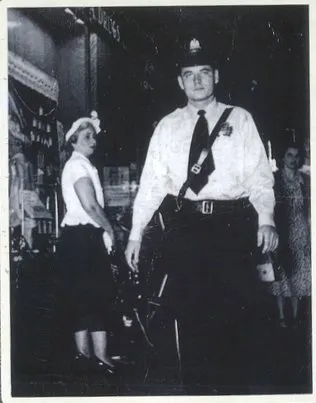

Henry Brown went running when he heard a cop was looking for him. In the 1920’s and 30’s he had been a blues piano legend but by 1954 he had become a Policy manager for an illegal numbers game. Charlie O’Brien was a vice cop for St. Louis Police Department as well as a music lover and blues detective. He was trying to find Brown for his friend Bob Koester so they could talk to him about his old recordings. O’Brien was just a blues documentarian at work.

Koester and O’Brien were the first in a long line of St. Louis blues lovers to document blues music and its long history in the river city. Koester, a jazz lover and student at St. Louis University, opened the Blue Note Record Store on Delmar Ave and launched Delmar records with a 1953 recording of the Windy City Six. He and O’Brien met as members of the St. Louis Jazz Club where Koester recruited him to try and find St. Louis prewar blues artists. It helped that O’Brien was a detective assigned to the downtown district where many musicians lived.

Their collaboration resulted in finding a series of forgotten artists that included Henry Brown, James Crutchfield, Walter Davis, Mary Johnson, Stump Johnson, Barrelhouse Buck McFarland, Speckled Red, James “Bat the Hummingbird” Robinson, JD Short, Henry Townsend, Big Joe Williams and many more. Koester’s research was documented in his newsletter, The Jazz Report, and the records he produced. Their efforts revived careers, produced new recordings and provided a wealth of material for jazz and blues documentarians.

Koester would build upon his St. Louis experience with his move to Chicago in 1958. Blue Note Records would be recreated as Jazz Mart Records and Delmar became Delmark. Charlie O’Brien would retire from the St. Louis Police Department in 1984 after 34 years of service. However, he remained a blues detective for many years.

Koester and O’Brien’s work inspired a new generation of blues detectives that is marked by the founding of the St. Louis Blues Society in 1984. Their efforts and the breaking of club color barriers helped revive the careers of a number of blues artists like Tommy Bankhead, Rudy “Silvercloud” Coleman, James Crutchfield, Bennie Smith, and Henry Townsend.

The St. Louis Blues Society also launched The Bluesletter whose revolving cast of writers (including this one) published hundreds of articles. The 1987 startup of a 43kw community owned radio station, KDHX (www.kdhx.org), with a roster of volunteer blues DJs/musicians like Ron Edwards, Art Dwyer, Tom “Papa” Ray provided a steady stream of blues music, interviews, history and stories.

The decade closed with the 1989 publication of Sweet, Hot and Blue: St. Louis’ Musical Heritage which quickly became a reference piece for blues researchers. The authors, Lyn Driggs, a local writer, and Jimmy Jones, a musician-singer and music teacher from Edgemont, Illinois profiled the lives and careers of 124 jazz and blues musicians including 57 in depth interviews.

In the last decade two books have provided the deepest exploration of St. Louis blues history. Kevin Belford’s 2009 book, Devil at the Confluence: The Pre-War Blues Music of St. Louis Missouri, is both scholarship and art. Belford, a renowned graphic artist and the author of several sports books, had begun a painting project to document the forgotten blues legends of the city.

As his research revealed more about what was missing than what was known it morphed into a coffee table worthy book that features lush graphics and period artwork. The history and musician profiles in it detail the major impact St. Louis had in the 20’s and 30’s. Lonnie Johnson, Roosevelt Sykes, Walter Davis, Victoria Spivey, and Peetie Wheatstraw led the charts for the number of sides cut and sales. The book also comes with a compilation CD of rare recordings from the Delmark Record archives.

The most recent blues detective to hit St. Louis is Bruce Olson. He spent much of his life in New York and Washington DC as a reporter but he will tell you, “I never got to tell the whole story.” He gave up reporting to become a blues club owner in Yachats Oregon. The Great Recession killed that after a 10 year run. Family and blues music led to a St. Louis retirement. But, that itch “to tell the whole story” still needed scratching.

After five years of research he finally got relief with the 2016 publication of his two volume history, That St. Louis Thing: An American Story of Roots, Rhythm, and Race. It documents the key role St. Louis played in the development of blues music and its many permutations. Olson weaves the threads of blues music, civil rights, and baseball into a historical tapestry that takes you from the 1800’s levee to modern day Ferguson. Each chapter is a standalone piece that moves between past and present with exciting digestible stories and segments of history.

Olson’s sense for detail provides context to the telling of real events immortalized in songs like Stagger Lee or Frankie and Johnny. Yes, those happened in St. Louis. He puts you in the Curtis Saloon on Christmas 1895 where Lee Shelton (Stagger Lee) shot Billy Lyons and tells how levee roustabouts spread the tale with their songs. His interviewing skills capture evocative moments like the night Tom Maloney, a well know local musician, was at the Club Imperial watching Ike and Tina Turner:

“First we get the band, the band does their thing, then the band goes into this boom-da-boom-da-boom-da-boom – the beat like galloping – then over to the left of the stage you see the Ikettes all standing in a line – like this engine ready to go down the tracks — and then – they hit it and come right up on stage all dancing and prancing – the strobe light goes on and you almost fall over – you don’t know what’s happened – and there’s these incredibly beautiful, vivacious gals with these miniskirts on – then there comes Tina, the queen of all of them — man it was something – and all the clocks stopped — time just stopped – and you were in a zone until they were done with us. It was quite fantastic.”

Since publishing the book Olson has used readings with accompanying musicians to educate folks about their city’s musical tradition. In October, at the National Blues Museum, he worked with the legendary keyboardist Ptah Williams to showcase Scott Joplin and discuss the relationship between black folk music and the development of Ragtime. The crowd loved it.

St. louis has always been proud of its musical heritage but it’s easy to forget and lose track of where it came from. It takes a village to remember. From Bob Koester and Charlie O’Brien to Kevin Belford and Bruce Olson and all our other blues detectives we know who we are and that our blues are true.

This story first appeared in the Dec.2018/Jan.2019 issue of Big City Rhythm and Blues

Author Bob Baugh